Wildfire Risk and Federal Cuts to NOAA, FEMA, and Climate Research: What Bay Area Communities Need To Know

Mapping the Federal Retreat on Climate Action — Part 2

By Keith Nickolaus, PhD, CRBA Writers Team

This post on wildfire risks is the second post in Climate Reality Bay Area’s ongoing series Mapping the Federal Retreat on Climate Action.

The series examines how recent federal cutbacks to climate science and key public agencies are reshaping environmental risk across the Greater San Francisco Bay region, why it matters locally, and how Bay Area communities can respond.

This post is focused on wildfire risks in the Greater Bay Area and explores how federal funding cuts to NOAA, FEMA, and climate science programs could weaken wildfire monitoring, early warning systems, and disaster response capacity in California. Focusing on local impacts, it outlines what these changes mean for public safety, community resilience, and why protecting science-based wildfire planning matters now more than ever.

Norther California Wildfire in 2017 (Photo credit: Frank Schulenburg, Wikimedia Creative Commons)

Overview

Across many countries and regions in the world over the past five years, wildfire is no longer just a moderate summertime risk. Countries from Brazil, Australia, Canada, and the United States (California) to Spain, Portugal, Greece, France, and parts of Asia (Indonesia, South Korea) have experienced recent, severe wildfires, often linked to climate change.

The bushfire activity across the states of Queensland (QLD), New South Wales (NSW), Victoria (VIC), South Australia (SA) and Western Australia (WA) and in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) was unprecedented in terms of the area burned in densely populated region (“Attribution of the Australian bushfire risk to anthropogenic climate change [Peer reviewed study],” Natural Hazards and Earth Systems Sciences, 2021).

2022 was the second-worst wildfire season in the European Union since 2000 when the Copernicus’ European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS) records began. Damages in 2022 exceeded those of 2021 and are only surpassed by those of 2017, according to data from the EFFIS Advance Report on Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2022, which offers a preliminary assessment of last year’s wildfires. (“The EU 2022 wildfire season was the second worst on record,” EU Joint Research Centre, May 2023).

Canada’s 2023 wildfire season was the most destructive ever recorded. By the end of the year, more than 6,000 fires had torched a staggering 15 million hectares of land. To put that in perspective, that’s an area larger than England and more than double the 1989 record. Normally, an average of 2.5 million hectares of land are consumed in Canada every year. And unlike previous years, the fires this year were widespread, from the West Coast to the Atlantic provinces, and the North. By mid-July, there were 29 mega-fires, each exceeding 100,000 hectares (“Canada’s record-breaking wildfires in 2023: A fiery wake-up call,” Natural Resources Canada, 2023).

World Weather Attribution, an academic collaboration studying extreme event attribution, found that hot, dry and windy conditions that fueled South Korea’s deadliest and largest ever wildfires [March 2025] were twice as likely and about 15% more intense due to warming caused primarily by the burning of fossil fuels. The fires broke out amidst record-breaking spring temperatures and resulted in over 30 fatalities, mass evacuations, the loss of some 5,000 buildings including some ancient sites, and burned 104,000 hectares, an area larger than New York City (“South Korea’s Deadliest Wildfires Twice As Likely Because of Climate Change: Study,” Earth.org, May 2025).

Closer to home, global warming results in increased heat, extended droughts, and more powerful winds — weather patterns and events that increase wildfire risks.

California experienced 7 of its 10 warmest years on record from 2012 to 2018, and warming is expected to continue. Sea level is predicted to rise 2 to 7 feet on California’s coast by 21,000, and the frequency of extreme events such as droughts, heat waves, wildfires, and floods is expected to increase.

— California’s Future: Climate Change, Public Policy Institute of California, Jan. 2020

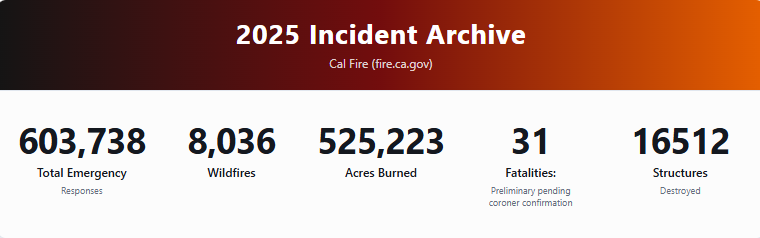

As a result, California is experiencing wildfires that are more intense, large, and damaging than what we’ve experienced on average in the last century. According to Calfire, fifteen of California’s twenty worst wildfires have occurred in the past 10 years (“Most destructive wildfires in California history,” ABC News, Jan. 2025).

Researchers at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography report that some models predict that “large wildfires (greater than 25,000 acres) could become 50% more frequent by the end of the century if emissions are not reduced, and the average area burned statewide would increase 77 percent” (“FAQ: Climate Change in California,” Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 2018).

The CRBA Writers Team pledges to share climate truths you can trust — not noise.

Sharing information grounded in facts, science, reputable media, and cited openly, our work cuts through disinformation to empower our community toward climate action and justice.

Wildfire Risks in California Today: A Perfect Storm Is Emerging

While California is no stranger to wildfire risks, the patterns taking shape today are alarming.

Fires of unprecedented size, intensity, and impact, and occurring year-round, are becoming the new norm — creating risk profiles that go well beyond the seasonal summertime forest and brush fires that older Californians recall from past decades.

Just as the threat level soars, the federal response is waning, with efforts to cut back funding for climate research and emergency preparedness and response.

Wildfires have long been a defining feature of life in California, thanks to topography and climate, with dry summers, strong offshore winds, and expanding urban development in fire-prone landscapes. Now, climate change is intensifying these conditions.

As a result, California wildfires are posing bigger threats today compared to past decades.

(Source: CA Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force, 2023)

Noteworthy, the Eaton and Palisades fires (2025) in LA County — these weren’t seasonal forest fires.

They actually broke out in mid-winter — fanned by not uncommon offshore winds — although this time the winds were exceptionally powerful, exceeding 50 mph with gusts up to 80 mph. The fire not only ravaged hillsides but also densely populated coastal housing developments.

According to Cal Fire, as reported by the Western Fire Chiefs Association (“Most Destructive Wildfires in California History”):

The Eaton Fire claimed 17 lives, destroyed 9,418 structures, and burned 14,021 acres.

The Palisades Fire claimed 11 lives, destroyed 6,837 structures, and burned 23,448 acres.

For California residents, warning signs came well ahead of 2025...

In 2017, for example, wildfires resulted in over 40 fatalities in Northern California in just one month (October). Half of the fatalities were from the Tubbs Fire. The fast-burning fire endangered thousands, killed over 20 people, and destroyed well over 5,000 structures, including nearly 3,000 homes (NBC News, Jan. 2019 and Wildfire Today).

In 2020 the August Complex Fire came to be known as California’s first “gigafire” — burning over 1 million acres across seven counties, larger than the area of Rhode Island (https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2020).

Largest Fires in California, 2020–2026

Among the largest and most notable California fires in the past five years:

August Complex Fire (2020) – Described as California’s first “gigafire,” burning over 1 million acres across seven counties.

LNU Lightning Complex (2020) – About 363,000 acres, one of the state’s largest fires, driven by August lightning storms.

North Complex (2020) – Roughly 319,000 acres in Butte, Plumas, and Yuba counties.

Dixie Fire (2021) – About 963,000 acres across multiple northern counties, one of the largest single wildfires in state history.

Caldor Fire (2021) – Around 222,000 acres in the Sierra Nevada, threatening South Lake Tahoe.

Federal Cuts to FEMA and NOAA

As California wildfires grow in intensity and scope, the federal agencies and resources that help communities anticipate, prepare for, and respond to wildfire risk are now facing staffing, funding, and research cuts.

At the beginning of 2026 FEMA “continues to face uncertainty amid abrupt cuts to disaster response staff and planning emails that show FEMA has been contemplating deeper reductions” (“Concerns Mount Over FEMA Staff Reductions,” Federal News Network).

In October of 2025, The Trump administration put a hold on billions of dollars in grant programs for disaster protection and delayed acting on governors’ requests for aid following disasters, according to Politico (“FEMA Canceled $11B in Disaster Payments to States,” E&E News, Jan. 2025).

NOAA lost about 30 percent of its funding in 2025, and it is set to spend 14 percent less for climate research than Congress mandated (“The Potential Impact of NOAA Budget Cuts on Commercial Real Estate,” Urban Land, Sept. 2025).

The White House budget proposal “eliminates all funding for climate, weather, and ocean Laboratories and Cooperative Institutes. It also does not fund Regional Climate Data and Information, Climate Competitive Research, the National Sea Grant College Program, Sea Grant Aquaculture Research, or the National Oceanographic Partnership Program" (“Congressional committees push back on Trump administration's proposed NOAA budget cuts,” ABC News, Jul. 2025).

This post looks at how recent real and proposed reductions like these increase wildfire risk for Bay Area residents by weakening the early-warning, planning, and response networks that help prevent small fires from becoming catastrophic ones.

Wildfire Risk Is a Climate and Information Problem

When we cut back the science that helps us anticipate extreme conditions, we’re not just losing information — we’re losing time. And time is what saves lives in wildfire and flooding events.

— Tom Murphree, Ph.D., retired climate scientist, Naval Postgraduate School

Wildfire is often framed as a land-management issue — fuel loads, forest thinning, or power lines. Those factors matter. But wildfire risk is also deeply tied to weather forecasting, climate monitoring, and emergency preparedness.

Some of the most dangerous fire conditions in California arise not from heat alone, but from combinations of:

strong offshore winds

low humidity

dry fuels

delayed or insufficient warnings

Accurately predicting these conditions is one pillar of wildfire defense — for prevention, mitigation, and preparedness — but it depends on continuous observation and monitoring.

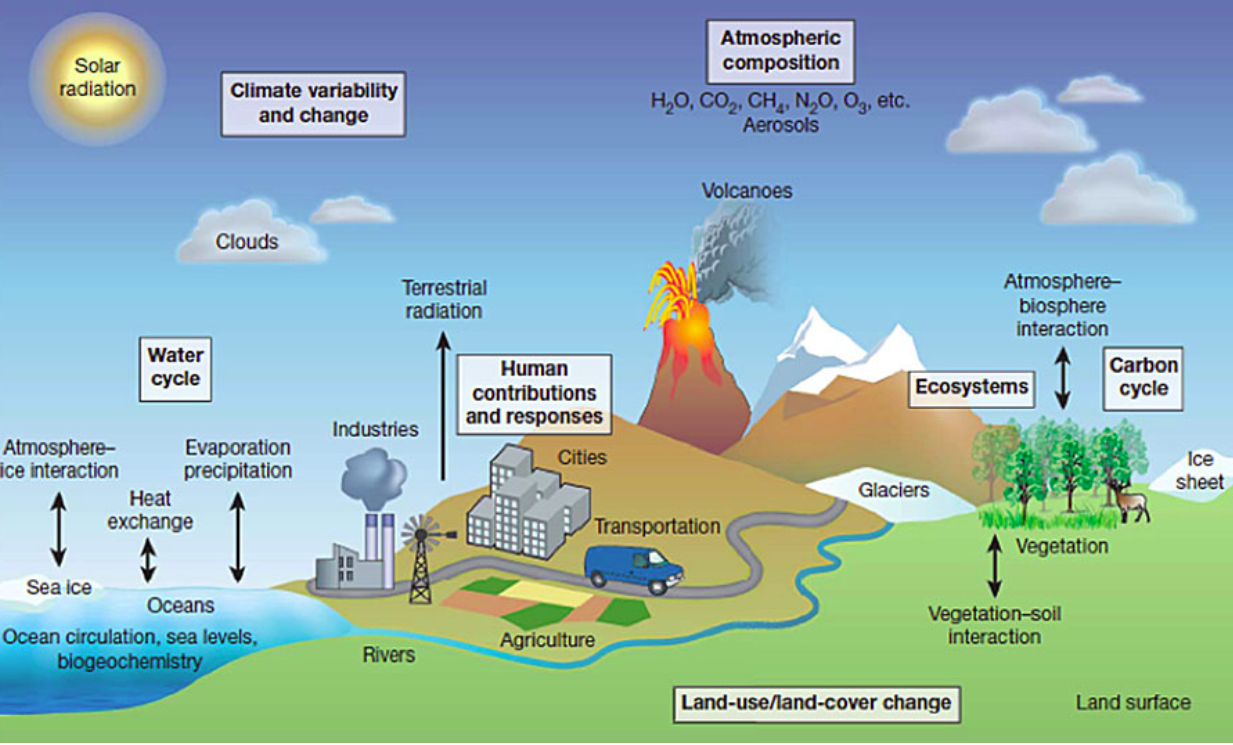

However, according to Bay Area climate scientist Tom Murphree, evolving and dynamic forces shape the climate conditions that impact wildfire risk profiles. This means monitoring goes beyond the atmosphere and beyond local weather conditions. Reliable prediction efforts involve ocean, atmosphere, land, and ice monitoring in regions around the globe, as well as unfettered information-sharing coordination across diverse international agencies.

Tom Murphree, PhD., Atmospheric Sciences, UC Davis

Murphree — a Bay Area resident — studied geology, physical oceanography, and atmospheric sciences at UC Davis and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography before going on to a 32-year career as a climate scientist with the Naval Postgraduate School.

For California residents wondering about the impact of federal cuts to climate science, Murphree wants them to understand how modeling wildfire conditions requires a holistic approach, one involving dynamic and inter-related environmental factors:

We know from the science of climate change that's been going on for decades that climate change driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases is producing more extreme events in weather and in climate. And just to be clear about what I mean by climate or the Earth's climate system, I'm referring to the atmosphere, the ocean, the land, and the organisms, all of which are involved in producing the physical environment in which we live.

The organisms that influence the chemistry of the atmosphere, which then affects the physics that determines where and when and how warm the ocean gets, when and where and how the precipitation or rain and snow fall over land. All of those components — of the atmosphere, the ocean, the land, and the organisms — influence the environment in which we live.

To illustrate how dynamic climate conditions can be, Murphree points out that just as we Californians are likely to be familiar with ways climate phenomena such as El Niño and La Niña can modulate seasonal weather patterns in different parts of California, so can the impacts of climate change alter how these systems interact with local environments. In other words, climate models and knowledge don’t live in a static knowledge stack, but require consistent data collection and analysis.

NOAA Climate Systems Model (Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory)

In addition, says Murphree, Californians alone obviously don’t have independent levers for mitigating climate trends and conditions. Behind the conditions we experience locally and statewide are global climate systems.

If you want to understand the global processes that are involved in climate variations and climate change, it's important to look where there's a lot of energy in the system... in particular in the western tropical Pacific Ocean, the eastern tropical Indian Ocean are where there's a lot of energy concentrated in the climate system. And variations in the storage of that energy, more energy being stored or less energy being stored, can lead to large variations in the climate system elsewhere in the world.

This kind of climate modeling framework — and its translation into practical information and reporting actions through state and local emergency managers, utilities, and fire agencies — requires consistent research efforts and happens largely under the umbrella of federal agencies such as NOAA and the National Weather Service.

When federal climate science capacity shrinks — as is happening under the current White House administration — the margin for error narrows.

When I asked Murphree if he saw any connections between recent catastrophic floods in places like Thailand (“Asia reels from deadly cyclones and monsoon rains,” CNN, Dec. 2025) and Texas (“National Weather Service defends its flood warnings amid fresh scrutiny of Trump staff cuts,” NBC News, July 2025) and the importance of climate science and forecasting, he said there are certainly real connections:

As we have made the earth warmer through our emissions of greenhouse gases, we've shifted the probabilities of what kinds of conditions are likely to occur toward more extreme conditions, extreme compared to what we're used to. We built our societies, our infrastructure, for example, based on assumptions about the environment in which our societies or infrastructure would need to exist.

And we underestimated the extreme events because we didn't anticipate climate change, at least not adequately when we designed these systems. And now we're seeing all over the world people are being impacted by these extreme events for which we are not prepared.

Moreover, says Murphree,

The Trump administration has made us less prepared by removing funding from the science that is needed to monitor the Earth's climate system and to help us get early warnings. The larger climate system is something that could impact for example how much rainfall Thailand gets, or that could impact the flow of moisture out of the tropical Atlantic into Texas that produces and impacts the rain and the flooding in Texas, just as it can impact droughts and heat — or flooding — where we live. So without that science, we're less prepared than we would otherwise be.

What Federal Cuts Mean on the Ground

1. Less Reliable Fire-Weather Forecasting

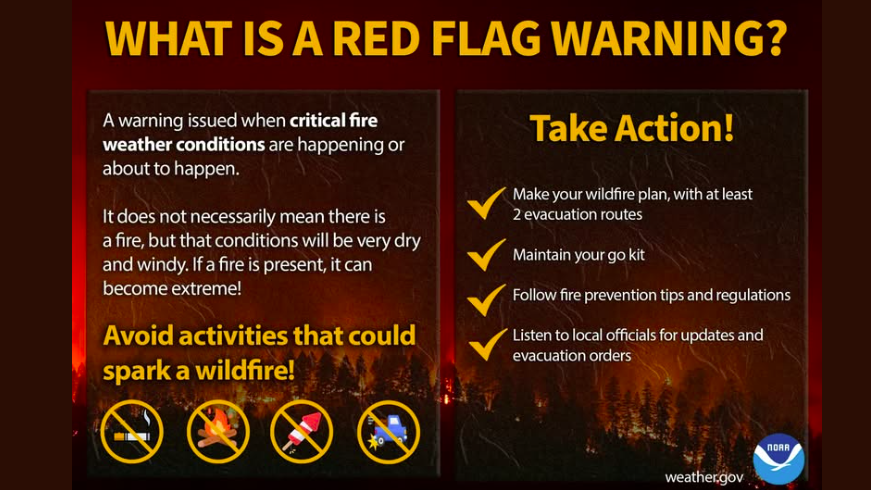

NOAA and the National Weather Service play a central role in issuing Red Flag Warnings, forecasting wind events, and monitoring large-scale climate patterns that influence fire behavior weeks or even months in advance.

Red Flag Warnings

While these warning systems help highlight when fire dangers are higher than ordinary, more comprehensive climate monitoring and forecasting is what reveals how overall conditions are changing the larger risk profile of impending fires. In recent years, for example, fires in California, on average, are not only more frequent, but causing greater destruction.

It seems that with each passing year, the average and structures destroyed break new records. People continue to be injured and die. Air quality may be impacted for more than 60 miles in every direction of the seat of a wildfire.

But now we’ve seen that wildfire preparedness relies not only on short-term forecasts but on long-lead predictions — the kind that help agencies pre-position resources and plan for elevated risk periods.

Recent local reporting has highlighted how layoffs and staffing shortages of National Weather Service staff (NWS operates under NOAA) at offices in California could reduce forecasting capacity and early warnings:

ABC7 Bay Area, “Fired NOAA scientists warn layoffs could impact weather forecasting along Northern California coast”

Monterey County Now, “At least six NOAA employees terminated at Monterey office”

Locally, Dalton Behringer, speaking in his capacity as the union steward for the Monterey office of the NWS Employees Organization said, "It may not be noticeable to the public right away… and we may not notice degradation in service right away, but down the road we will start to see issues."

The less lead time we have, the more likely it is that people won’t get out at all — not because they ignored warnings, but because those warnings came too late.

— Tom Murphree, Ph.D., retired climate scientist, Naval Postgraduate School

2. Emergency Management With Fewer Tools

Wildfire response is coordinated across local, state, and federal levels. FEMA plays a critical role in:

pre-disaster mitigation funding

emergency coordination

post-fire recovery support

Homeland Security — Then and Now…

November 2022

FEMA, under the Department of Homeland Security during the Biden administration announces $51 million in Firefighter Grants. — Homeland Security Today

November 2025

“President Trump and other Administration officials, such as Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, have repeatedly said they intend to dismantle or significantly restructure FEMA. FEMA staffing decreased 9.5 percent between January and June 2025 primarily due to the Administration’s workforce reduction program, leaving the agency less prepared to deal with a major disaster.” — Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

(Photo credit: Homeland Security Today)

Bay Area reporting has raised concerns that federal funding freezes and staffing reductions are already affecting preparedness, particularly during years with overlapping disasters.

John Wurdinger, Battalion Chief with Menlo Park Fire Protection District and Program Manager for Task Force 3 Special Operations Team says federal funding “isn’t adequate for what is needed to maintain the [specialized emergency response] teams” and not keeping pace with the growing scale and frequency of deployments.

“San Francisco officials have warned that with climate disasters expected to multiply in intensity and frequency, federal resources at any given point will be even more scarce.” (“FEMA cuts could hurt an already fragile disaster response in California,” Axios SF, March 20205)

“Recently the Government Accountability Office sounded the alarm on FEMA’s ability to respond to multiple disasters as a result of the agency’s severe understaffing, as the current administration aims to shrink it.” (“Cuts to FEMA has local first responders concerned over federal disaster support,” CBS Bay Area, Sept. 2025)

Just as cuts to climate research are adding risks by reducing capacity for early warning and prevention efforts, cuts to FEMA mean increased odds of inadequate response efforts — if and when new fires emerge, including wildfires with increased intensity and far less seasonal predictability.

3. Planning Blind Spots in a Changing Climate

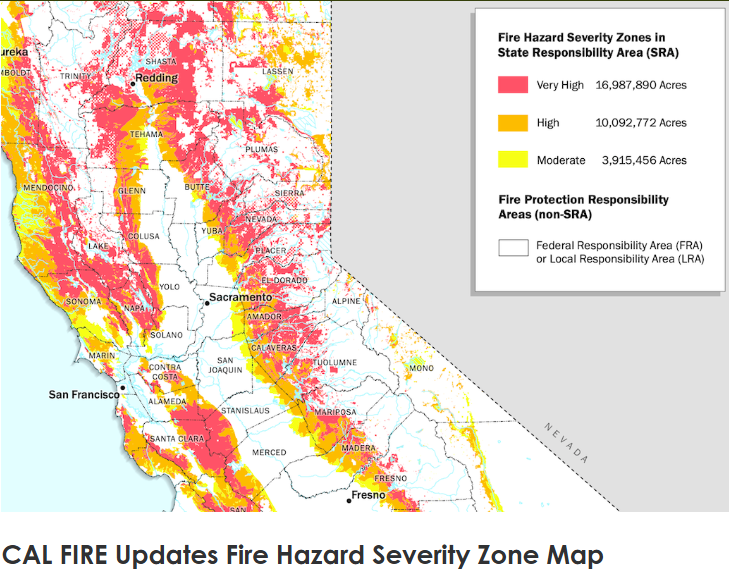

Climate change is not only increasing wildfire risk — it’s also changing where and how fires occur.

Areas that historically faced lower risk — including parts of the Bay Area’s urban-wildland interface — are now experiencing conditions that favor rapid fire spread.

Murphree noted that California depends heavily on global observation systems to understand what is coming locally. Monitoring those systems requires sustained investment in climate science and international data sharing.

When those research and information sharing systems are weakened, communities lose the ability to see risk coming far enough in advance to plan effectively.

Why the Bay Area Is Especially Vulnerable

The Greater Bay Area sits at the intersection of multiple wildfire risk factors:

dense population near fire-prone hills and open space

critical transportation corridors vulnerable to closure

aging infrastructure sensitive to wind and heat

communities with uneven access to evacuation resources

Past disasters — from the Oakland Hills Fire to more recent North Bay fires — have shown how quickly wildfire can overwhelm even well-resourced regions. In those moments, preparedness depends on coordination, communication, and credible science.

Federal cutbacks do not dismantle these systems overnight — but over time what happens?... Over time the impact could include much greater loss of property and life.

The Importance of “Long-Lead” Forecasting

As federal agencies reduce commitments to NOAA and FEMA resources and to climate research — locally, nationally, and globally — the cutbacks will almost certainly erode forecasting reliability and create scenarios that conceal growing systemic gaps and failures — increasing the likelihood that warnings arrive late, resources that do arrive are stretched thin, or recovery takes longer than communities can afford.

When I asked Murphree about the potential impacts of federal cuts to NOAA and FEMA on residents of the Greater SF Bay/Delta Regions — in particular with regard to forecasting and preparation for threats such as wildfires — he was most concerned about the impact cuts are likely to have on what he calls long-lead predictions: “predictions at lead times of a couple of weeks to a couple of years or longer help people more adequately plan and prepare for what the environmental conditions are likely to be.”

This leaves Murphree worried that “in the Bay Area and in Western North America we’re not going to be adequately prepared with scientific information about what’s coming.”

Key Takeaways

Wildfire risk is not just about fire suppression; it is about forecasting, preparedness, and early warning.

Federal climate science and weather monitoring play a foundational role in California’s wildfire readiness.

Cuts to NOAA, FEMA, and related research reduce lead time and increase uncertainty at moments when clarity is most needed.

Bay Area communities face compounding risk as climate change accelerates and federal support retreats.

What You Can Do

Core actions to consider now:

Follow Climate Reality Bay Area’s newsletter and social channels for updates.

Share this post with neighbors, parent groups, community organizations, and local leaders. (Sign up here.)

If you have been impacted by wildfire or smoke, consider sharing your story in the comments.

Join a Climate Reality Bay Area Policy Action Squad other CRBA team that’s a fit for your interests and aptitudes — and get connected with other Bay Area residents advocating for climate action.

Wildfire-specific actions:

Sign up for Red Flag Warnings and local emergency alerts through your county, CAL FIRE, and the National Weather Service. (Check out READY.GOV/ALERTS and Alert the Bay.org)

Learn more about wildfire safety planning; participate in defensible-space and wildfire-preparedness efforts in your community by connecting with your local Fire Safe Council resource hub (Find A Fire Safe Council)

Attend county wildfire-mitigation meetings and submit public comments urging sustained investment in forecasting, preparedness, and climate science.

Accessing your local wildfire protection plan:

Other resources:

CAL FIRE https://www.fire.ca.gov and CAL FIRE PREVENTION https://www.calfireprevention.org/

County Offices of Emergency Services, for local evacuation plans and alerts among other resources

Bay Area Air Quality Management District — https://www.baaqmd.gov

East Bay Wildfire Coalition of Governments (meeting notices and materials, background information, and updates)

Next in this series:

Water, Coasts, and the Bay-Delta Under Stress — How federal cuts are reshaping flood risk, fisheries, and the systems that protect California’s most vital ecosystems.

Click Below To Learn More About CRBA and How To Get Connected!