Water Frontlines: How Federal Cuts May Increase Flood and Sea Level Risks in the Bay Area

Mapping the Federal Retreat on Climate Action — Part 3

By Keith Nickolaus, PhD, CRBA Writers Team

This post is on risks from floods and sea level rise and marks the third post in Climate Reality Bay Area’s ongoing series Mapping the Federal Retreat on Climate Action.

The larger series — examines how recent federal cutbacks to climate science and key public agencies are reshaping environmental risk across the Greater San Francisco Bay Region, why it matters locally, and how Bay Area communities can respond.

Our previous post in the series focused on wildfire risks in the Greater Bay Area.

This post — explains the many ways federal cuts to NOAA, FEMA, the EPA, and climate science research can heighten risks from flooding and rising sea and groundwater levels. Dwindling resources for forecasting, modeling, and monitoring mean early warnings and long-term planning become less reliable — increasing uncertainty and weaking safeguards even as water-related climate risks are accelerating.

Keep reading to learn about key risks stemming from federal cuts, hear what local scientists think, and find ways to take action.

California National Guard Soldiers support local first responders in rescue operations due to flooding in Monterey County, California, March 11, 2023. (photo courtesy of the 1-184 Infantry Regiment, California National Guard)

With drought and wildfire getting so much attention, Californians may have lost sight of extreme flooding… There is potential for bad wildfires every year in California, but a lot of years go by when there’s no major flood news. People forget about it.

— Daniel Swain, UCLA climate scientist

It is essential the region clearly understands our shared vulnerabilities to flooding and sea level rise so that we can implement strategies necessary to make our communities and transportation infrastructure more resilient now and into the future.— “Regional Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Study,” Adapting to Rising Tides Bay Area, March 2020

Overview: Climate Risks, Federal Cuts, and Bay Area Water Frontlines

Water — whether too much or not enough — has become one of the most immediate climate frontlines facing Bay Area communities. While droughts have long shaped California’s water story, recent years have underscored a different and growing set of risks: heavier rainfall, flooding, and groundwater andsea level rise.

From flooded roadways during major winter storms to coastal overtopping during king tides, these impacts are already serving as catalysts for accelerating and shaping comprehensive regional planning and resilience efforts.

When major storms channel for days over the region runoff, flooding, and tidal surges can result in significant disruptions, property loss, and even loss of life.

Sea level rise can amplify the threats, pushing water farther inland, creating more flooding and risk factors, and hindering emergency responders.

Now, just as climate change continues to add to the magnitude of future storms and to accelerate sea level rise — creating greater urgency for reliable forecasting and for projecting which Bay Area regions, infrastructure, and communities might be most vulnerable — the federal government is dialing down commitments to agencies like NOAA, FEMA, and the EPA, and reducing investments in climate research and reporting.

Flooding, extreme storms, and sea level rise are projected to become bigger and bigger risk factors in the coming decades, with Bay Area seashores and diverse waterways making communities in our region highly vulnerable and making adaptation efforts colossal and complex. This article examines how federal cuts to forecasting, modeling, and monitoring systems could weaken early warnings and long-term planning, increasing uncertainty just as water-related climate risks accelerate.

The CRBA Writers Team pledges to share climate truths you can trust — not noise.

Sharing information grounded in facts, science, reputable media, and cited openly, our work cuts through disinformation to empower our community toward climate action and justice.

Climate-Driven Water Risks Facing Bay Area Communities

Unfortunately, much of our region was not designed to be safe from unanticipated future flooding… Many of the region’s existing sea walls, levees, and flood control structures are inadequate, seismically unsafe, or in need of maintenance and upgrades, while other areas have little or no flood protection at all.

— “Raising the Bar on Regional Resilience”(Draft Report, September 2017), Bay Area Regional Collaborative

Climate-driven water risks in the Bay Area are becoming more frequent, more intense, and more difficult to manage.

⚠️ Extreme rainfall events are increasing the likelihood of flash flooding in urban areas, particularly where aging stormwater infrastructure was not designed to handle today’s volumes of runoff.

⚠️ Rising sea levels are steadily reshaping conditions along the Bay’s shoreline, where coastal flooding increasingly coincides with storms and high tides. In low-lying communities, even relatively modest storms can now produce outsized impacts, particularly when storm surge, runoff, and elevated tides occur simultaneously.

⚠️ Legacy contaminants are present in many SF Bay Area localities, compounding other more obvious dangers associated with flooding and groundwater rise and leaving a patchwork of communities, ecosystems, and water sources vulnerable to contamination.

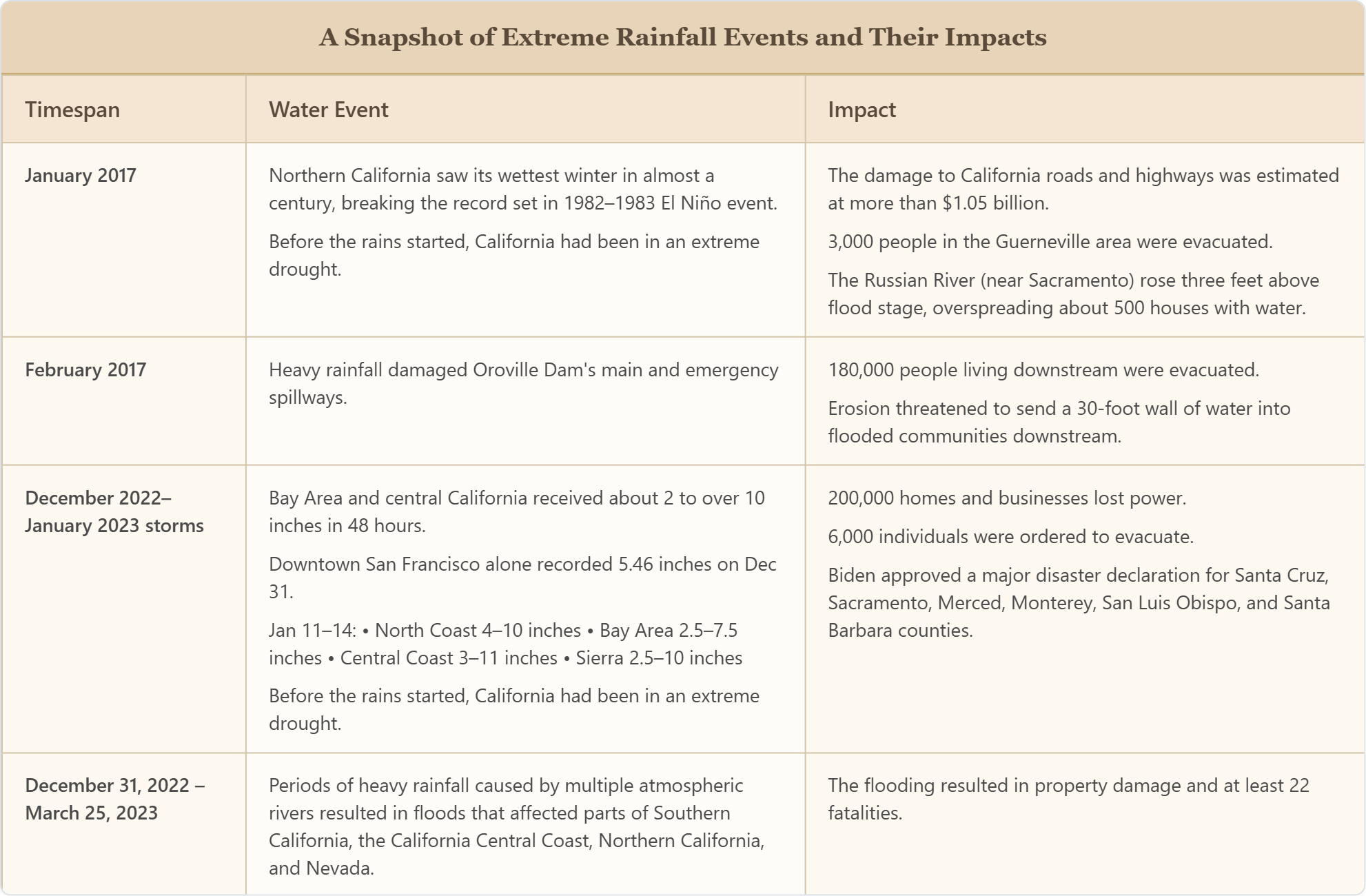

Storms & Rainfall

The present risks from 100-year megastorms are elevated by climate change, so the Bay Area Region has significant vulnerability to flood waters and sea level rise, just as it does to wildfires, droughts, and earthquakes.

🔑 The present risks from 100-year megastorms are elevated by climate change, so the Bay Area Region has significant vulnerability to flood waters and sea-level rise, just as it does to wildfires, droughts, and earthquakes.

Is climate change truly affecting rainfall levels, runoff, and storm and wind intensity?..

It’s an important question and a factor when it comes to modeling and projecting future risks.

Researchers don’t know how much global warming might be contributing to the frequency and intensity of specific storms, even extreme ones (“For all their ferocity, California storms were not likely caused by global warming, experts say,” Los Angeles Times, 19 Jan, 2023).

This means acknowledge uncertainty about how much climate change is contributing to specific storms or specific seasonal events or patterns.

However, many researchers agree — the impacts of climate change and global warming does create an overall higher risk profile for Bay Area flooding — with “climate models predicting more frequent mega-storms fueled by warming oceans and a thirstier atmosphere due to global warming” (Los Angeles Times, 19 Jan, 2023).

🔑 While it can be hard to know with certainty how much global warming and climate change impact more isolated weather events, there’s a strong consensus among scientists that warming oceans and warmer temperatures will increase local risks associated with heavy rains, mountain runoff, and sea level rise.

In the Bay Area, this has meant more frequent atmospheric river storms capable of delivering months’ worth of rain in just a few days. During recent winters, these storms have triggered flooding along creeks and rivers, overwhelmed urban drainage systems, and disrupted transportation corridors throughout the region.

According to climate scientists Daniel Swain, PhD (UCLA) and Xingying Huang, PhD (National Center for Atmospheric Research):

A growing body of research suggests that climate change is likely increasing the risk of extreme precipitation events along the Pacific coast of North America, including California, and of subsequent severe flood events” (“Climate change is increasing the risk of a California megaflood, Science Advances, 12 Aug 2022).

In addition, a warming climate can mean less overall yearly precipitation, but heavier rain events. In fact, over the past 10 years, our region has seen major storms and rainfall events occur on the heels of significant droughts!

This drought vs. rainfall pattern is due in large part to warming ocean temperatures, but also because warmer temperatures turn would-be High Sierra snowfall into rain that increases runoff into streams, rivers, and plains below. This means rising global temperatures impact the greater Bay Area with increasing runoff from higher elevations in the midst of heavy storms, while also exacerbating drought conditions overall (“Climate change makes catastrophic flood twice as likely, study shows,” University of California News, 18 Aug, 2022).

See “List of California Floods” Wikipedia.org

We've had less people die in the last two years of major wildfires in California than have died since New Year's Day related to this weather.

— Statement from Governor Gavin Newsom in wake of Jan 2023 storms (Fox News, 10 Jan 2023)

Rising Sea Levels & Groundwater

Sea level rise is steadily increasing baseline flood risk along the Bay’s shoreline. Even in the absence of major storms, higher tides are beginning to affect low-lying neighborhoods, wetlands, and critical infrastructure.

According to researchers with NOAA’s Office for Coastal Management (NOAA OCM) and the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC):

As sea levels rise, groundwater and salinity levels are also predicted to rise. These two factors provide additional sources of flooding and vulnerability to infrastructure and natural systems. When storms do arrive, elevated sea levels can amplify flooding, pushing water farther inland and complicating emergency response.

Rising sea level is unlike any disaster we have seen before. As opposed to temporary flooding from King Tides or storms, the encroachment of the bay onto our shoreline will be permanent, widespread, and constantly worsening. Without proactive action, widespread consequences will be felt throughout our transportation system, utilities, housing markets, ecosystems and recreation spaces, economy, and, most critically, the region’s residents, especially the most vulnerable residents.

— “Regional Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Study,” Adapting to Rising Tides Bay Area, March 2020

Vulnerability to sea level rise isn’t just to homes built on shorelines — though there are thousands of homes like these across local oceanfronts and the many bay and delta shorelines, streams, and rivers that crisscross the entire Bay Region. The fact is, risks from sea level rise are almost certain to have significant impacts on everyone in the greater Bay Area.

Sea level rise impacts could reduce the competitiveness of the region in terms of jobs, production of resources, tourism, and attracting and maintaining residents. Many residents could experience a significant decline in their quality of life, while others with means may retreat to higher and drier locations, further exacerbating inequality.

— “Regional Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Study,” Adapting to Rising Tides Bay Area (ART Bay Area), March 2020

Here are just some of the anticipated impacts of sea level rise highlighted by forecasters working with NOAA and the BCDC:

Risks to Bay Area Communities From Projected Sea Level Rise

⚠️ Groundwater intrusion near the Bay and farther from the shoreline, posing threats to water quality

⚠️ Nearly 13,000 existing housing units that will no longer be habitable, insurable, or desirable places to live

⚠️ Nearly 104,000 existing jobs that will either need to relocate or be lost

⚠️ Over 20,000 acres of habitats for depressional wetlands, lagoons and tidal marshes that will no longer be able to support a diversity of wildlife, habitat for endangered species, support recreation and tourism, provide climate resilience, among other ecosystem services

⚠️ Over 5 million highway vehicle trips daily that will need to be rerouted to surface streets, other highways, or transit, or not taken

Source: “Short Report: Summary of Regional Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaption Study,” Adapting to Rising Tides Bay Area, March 2020

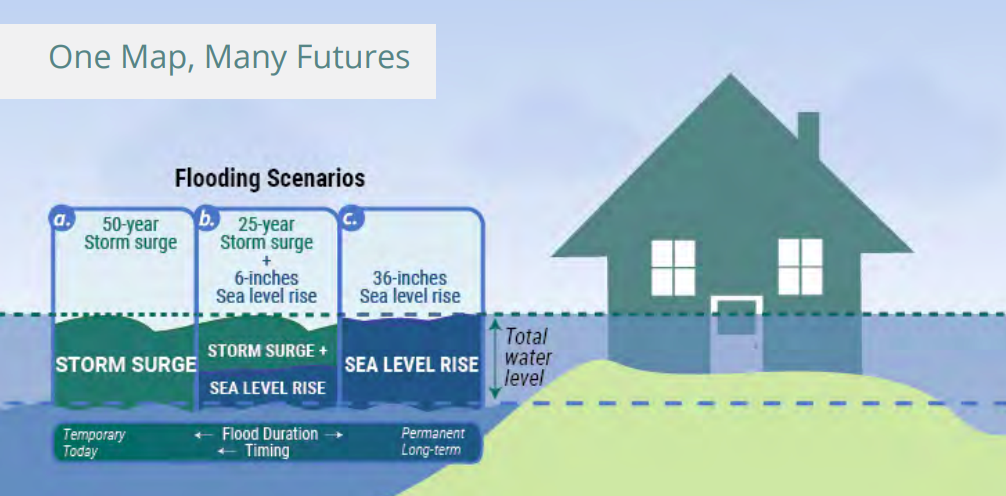

🛠️ To learn more about flood risk across greater Bay Area regional shorelines and communities, check out Bay Shoreline Flood Explorer. This interactive mapping tool, provided by Adapting to Rising Tides, allows you to forecast how your community might be impacted by sea level rise and related tidal and flood risks going into the future.

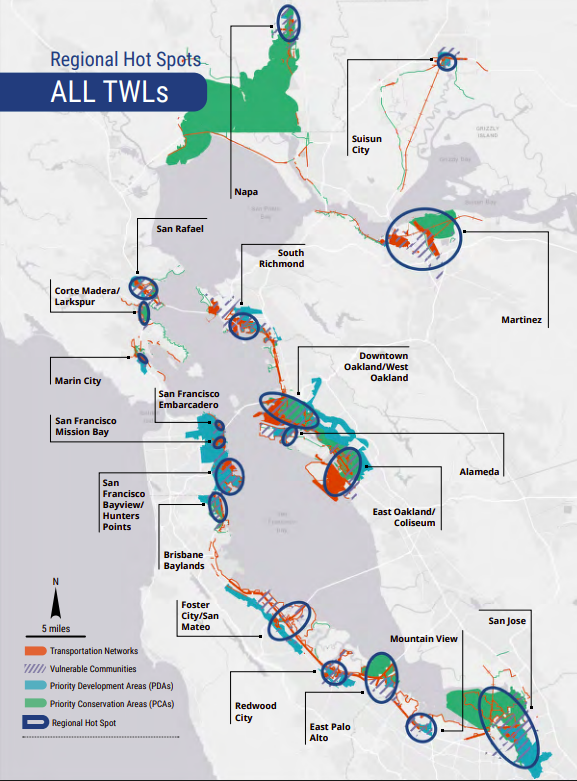

A Map of Sea Level Rise “Hot Spots” in the Greater East Bay Region

Image Source: Adapting to Rising Tides Bay Area

Risks From Migrating Contaminants

Rising seas in the Bay Area threaten not only homes and infrastructure but can easily destabilize contaminants long-buried in the soil (“Ask An Expert: What Flood Risk Does the Bay Area Face?”Save the Bay, March 2023).

As sea level and connected groundwater levels rise, water can reach previously remediated sites, which capped contaminated soils and waste assumed to be safely isolated. This increases the risk these contaminated soils and waste will disperse to surrounding neighborhoods, stormwater systems, and watersheds.

Even small changes in groundwater elevation — on the order of a few centimeters — can alter flow directions in complex urban sub-surfaces with pipes and utility corridors, creating new pathways for contaminants to move, potentially exposing people to contamination risk, even in places that have no visible standing water (“Sea level rise, groundwater rise, and contaminated sites in the San Francisco Bay Area, and Superfund Sites in the contiguous United States,” Kristina Hill et al., UC Berkeley researchers Kristina Hill et al., Dryad, May 2023).

A recent UC Berkeley research study suggests that groundwater rise may impact roughly twice as much land area as coastal inundation alone.

Under plausible sea level rise scenarios, these rising waters could makethousands of contaminated sites vulnerable.

Here’s how reporters at UC Berkeley Research News summed up the local risk factors:

Over the next century, rising groundwater levels in the San Francisco Bay Area could impact twice as much land area as coastal flooding alone, putting more than 5,200 state- and federally-managed contaminated sites at risk. Many of these sites are near communities already burdened with high levels of pollution, including West Oakland, the waterfront in Richmond and Hunter’s Point in San Francisco.

This means flood and sea level rise planning in the Bay Area must go beyond surface water and levees to include mapping groundwater rise, reassessing cleanup and capping strategies, and prioritizing remediation and infrastructure upgrades in neighborhoods where migrating contaminants pose serious long‑term risks to life, health, and property (“Regional Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Study,” Adapting to Rising Tides Bay Area, March 2020)

Managing the Risks…

Managing these risks depends not only on physical infrastructure, but on the ability to anticipate hazards before they unfold.

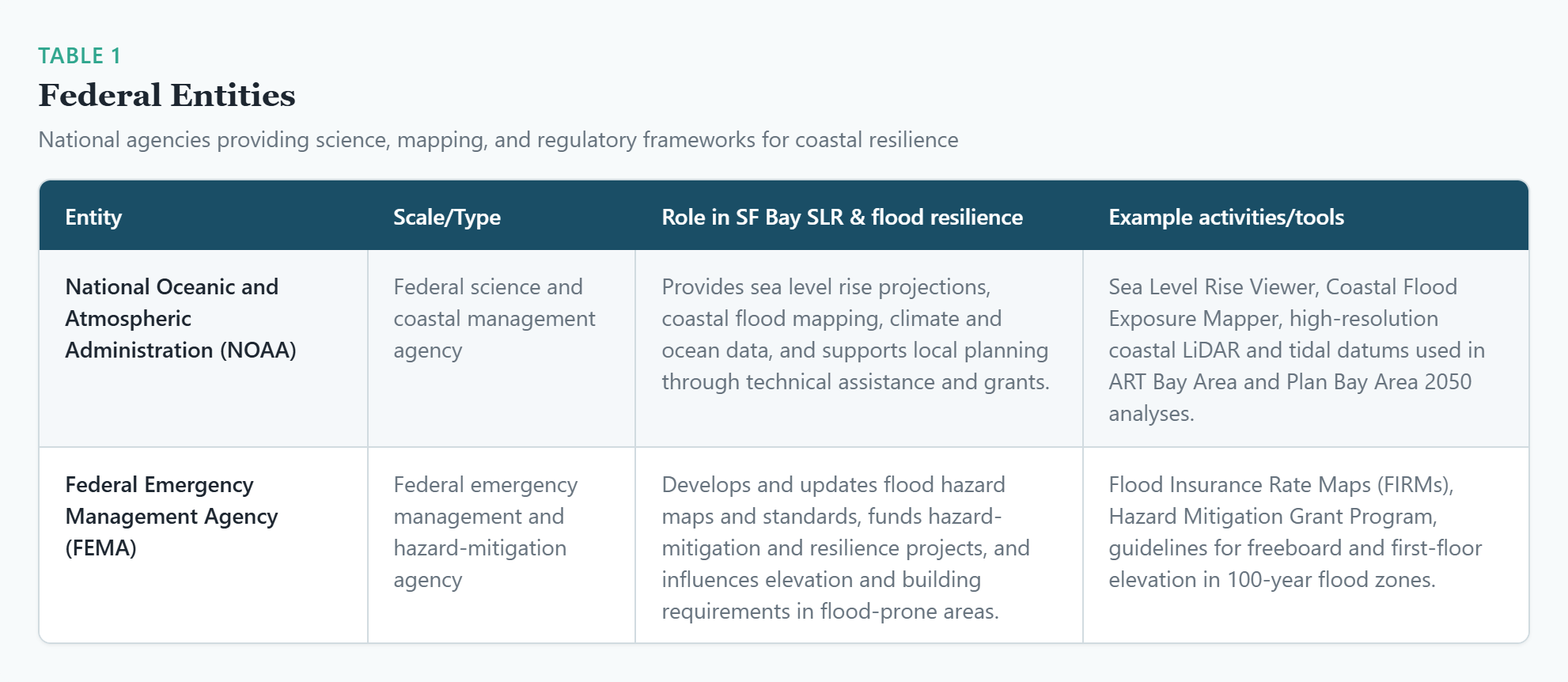

That foresight relies on climate science, forecasting, and monitoring systems — many of which are supported by federal agencies such as NOAA, FEMA, EPA, and the Bureau of Reclamation.

As federal staffing and funding cuts begin to take effect, questions are emerging about how resilient those systems will be just as climate risks continue to accelerate.

Photo: Flood under the Old Route 49 bridge crossing over the South Yuba River in Nevada City, California, saw local and regional visitors during the atmospheric river event across Northern California on January 9, 2017.

Photo Credit: Kelly M. Grow/ California Department of Water Resources - California Department of Water Resources

To learn more, we interviewed several local scientists and climate experts for this series.

These experts told us that climate-related risks in the Bay Area are no longer isolated or episodic.

Instead, they are fueled by climate extremes and global warming and more interconnected and compounding than ever. These warnings spotlight the need for reliable forecasting, modeling, and early warning systems that help Bay Area communities prepare for what may come next.

At the same time, it’s hard to predict for certain how much the federal retreat from agencies on the frontlines of forecasting, climate research, and emergency planning will impact public safety, resilience planning, and emergency response capacity.

Climate Forecasting and Modeling: Why They’re Critical for Flood and Storm Preparedness

Climate forecasting and modeling play a central role in reducing water-related risk — not by eliminating uncertainty, but by narrowing it enough to support timely, informed decisions.

In a region like the Bay Area, where floods can unfold quickly and impacts vary dramatically by location, the difference between early, and reliable warnings vs. delayed or uncertain ones can impact the consequences of major weather events, as measured in property damage, service disruptions, and lives put at risk.

Short-term weather forecasting informs preparation and response efforts:

Helping emergency managers anticipate when extreme rainfall or storm surge is likely to occur

Guiding decisions about issuing flood warnings, closing vulnerable roadways, staging emergency personnel, and coordinating with utilities and transit agencies

This means that even modest improvements in forecast lead time can provide communities with critical hours to prepare.

Long-range climate modeling also contributes to public safety:

Projections of future rainfall patterns, sea level rise, and storm intensity all help frontline agencies plan for advance warning and preparation efforts

Informs risk assessment, engineering standards, and a wide range of civic planning and adaptation efforts, such as where levees should be reinforced, how stormwater systems should be upgraded, and which neighborhoods may face heightened risk in the years ahead

Police in San Mateo swam to a partially-submerged Mercedes to rescue the driver after the vehicle became stranded in floodwaters at an underpass during sudden flooding in intense rain. Within hours the flooding at 42nd Avenue and Pacific Boulevard was over and the intersection re-opened. Nobody was hurt, and the car was towed (NBC Bay Area News, 26 November, 2019).

Photo Credit: Bruce Washburn, www.flickr.com/btwashburn

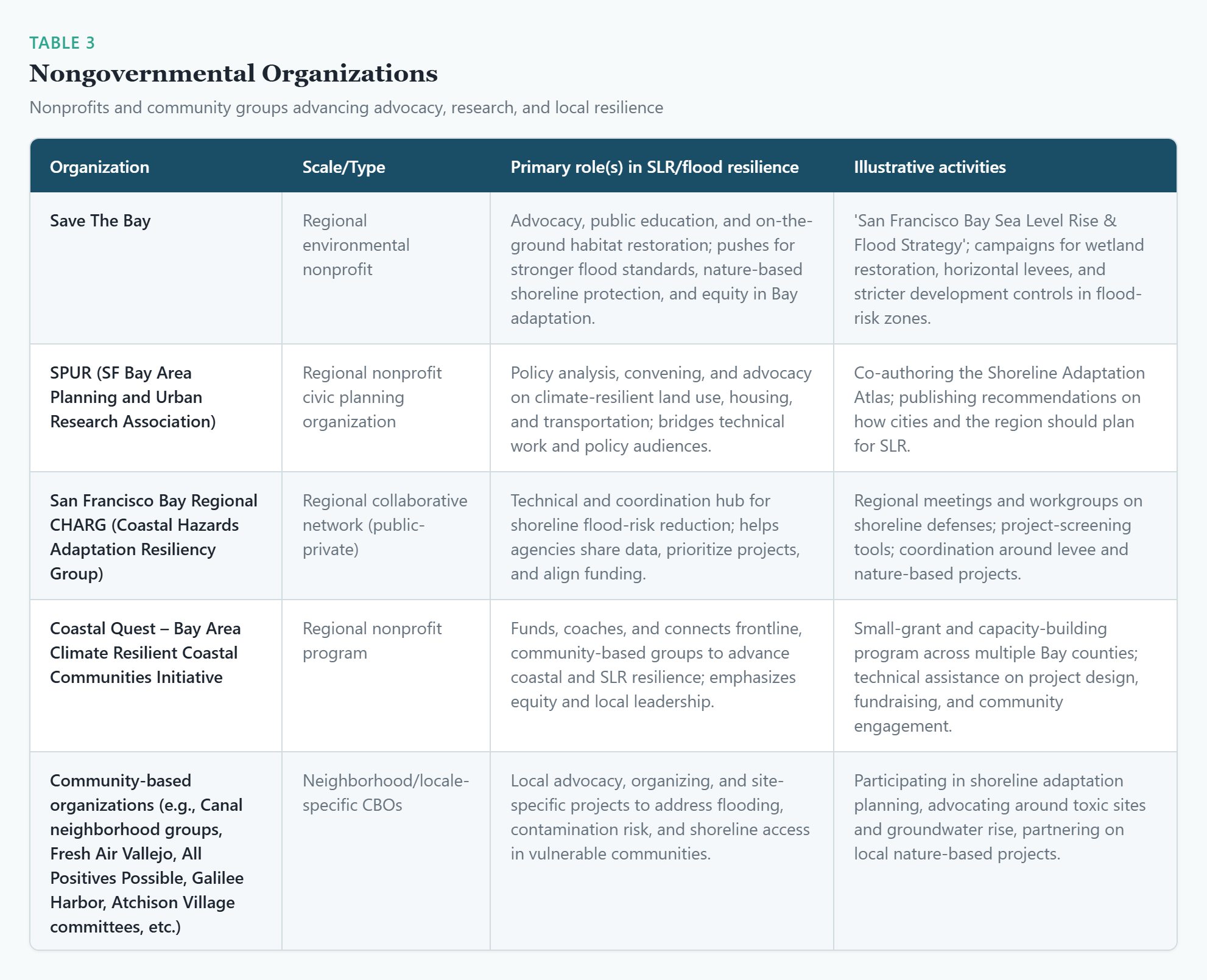

Some modeling and mapping tools are also accessible to ordinary residents.

For example, sea-level-rise mapping tools, like ART’s Bay Shoreline Flood Explorer, are easy to find and use. These interactive maps rely on high-resolution elevation data, coastal studies, and shoreline research to show what flooding could look like across dozens of possible futures — not just one best-guess scenario.

However, tools like these, and their wide availability, are made possible through a network of working partnerships and specialized contributions. In the Bay Area this work happens through collaborations that include key federal agencies — such as FEMA and NOAA — along with non-federal entities such as the California Ocean Protection Council, the SF Estuary Institute, SF Bay Regional CHARG and more.

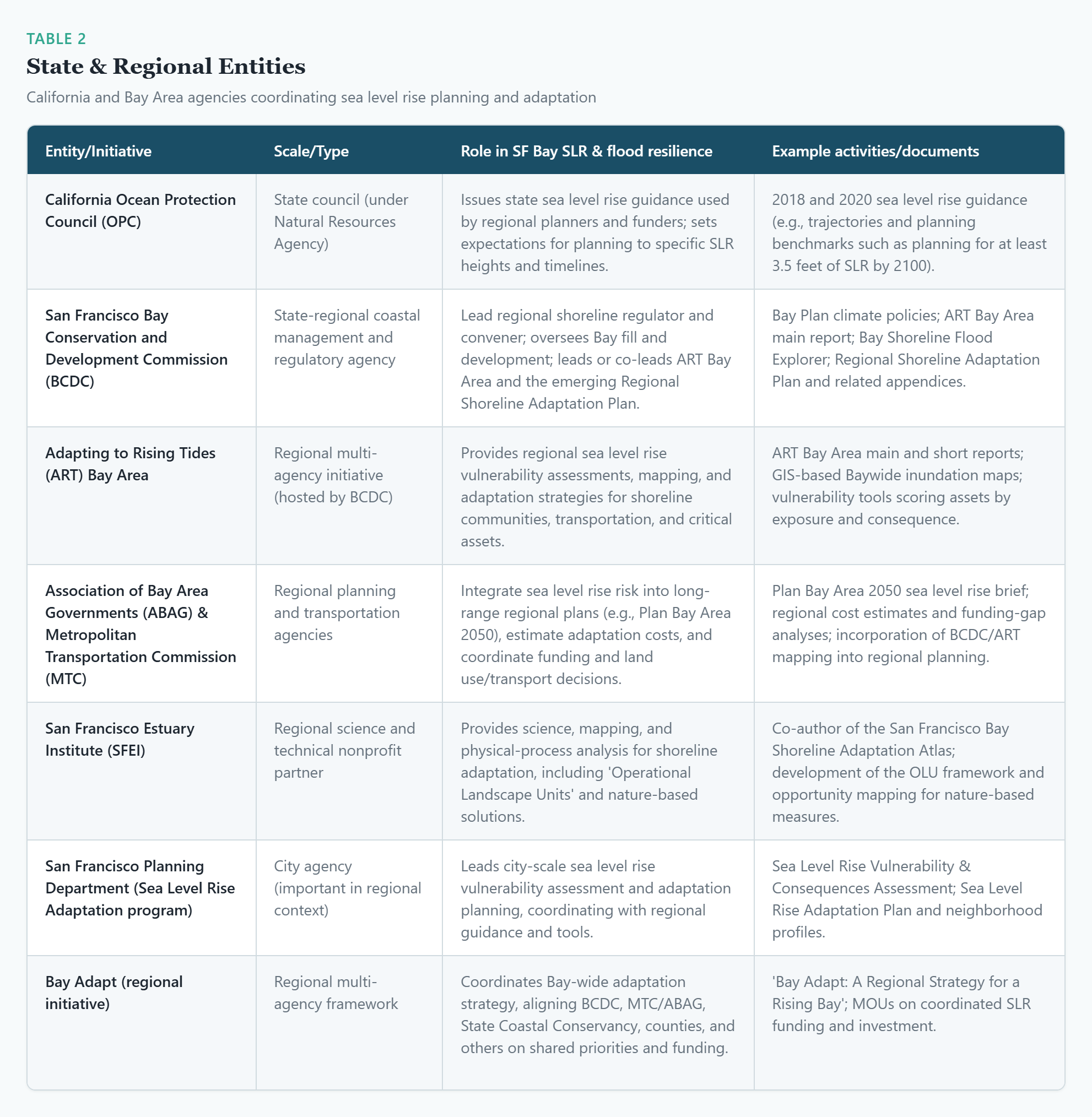

The Agency Landscape:

Key Entities + Roles They Play in Water Monitoring, Planning, and Policy Action

The Importance of Advanced Modeling and Close Coordination

At the end of the day, models and forecasts provide invaluable data and insights for civic planners, civil engineers, and legislators — data that informs how today’s shoreline could be affected under a wide range of sea level and tide combinations, helping stakeholders at the state, regional, and local levels see what’s at risk if no action is taken.

Indispensable to these projections are:

continuous data streams from monitoring networks — tracking precipitation, river levels, soil moisture, tides, and ocean conditions

experienced scientists and forecasters — able to interpret signals, recognize emerging threats, and communicate risk clearly to decision-makers and the public

As retired Bay Area climate scientist Tom Murphree (PhD, Atmospheric Sciences) pointed out, “the larger climate system… can impact droughts and heat — or flooding — where we live. So without that science, we’re less prepared than we would otherwise be.”

This challenge is especially pronounced in the context of atmospheric river storms, which can evolve rapidly and produce highly localized impacts. Accurately forecasting where these storms will concentrate rainfall — and how that rainfall will interact with rivers, reservoirs, and coastal conditions — requires both advanced modeling and close coordination among agencies.

An Example of Modeling — In the Words of Climate Scientists

We found that of the top 4 ranked megastorm events (as quantified by California-wide cumulative 30-day precipitation),all 16 events across the four single-model large ensembles have larger cumulative precipitation in the warmer future scenario versus their counterparts drawn from cooler historical climate snapshot period (fig. S1). We further show that hourly precipitation maxima are also higher in future versus historical megastorm events in all four large ensembles…

— Xingying Huang and Daniel Swain, “Climate change is increasing the risk of a California megaflood,” (Science Advances, 12 Aug, 2022)

Xingying Huang is a scientist withClimate and Global Dynamics Laboratory, National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado.

Daniel Swain is a researcher with the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Mapping and Modeling

When enough modeling data is available, digital mapping tools can highlight a range of possible scenarios based on variables that span time, geographical factors, and diverse weather scenarios. As researchers at ART (Adapting to Rising Tides) put it: you can create one map projecting different future scenarios!

Sea Level Rise Projections: SF Bay East Bay

Present 2060 (Projected) 2080 (Projected)

What’s Being Lost: How Federal Cuts Undermine Climate Science and Water Monitoring

The impacts of federal cuts to climate science are not always immediate or easy to see. Unlike a cancelled construction project or a shuttered facility, reductions in forecasting, monitoring, and research capacity tend to unfold quietly, over time. Yet these systems form the backbone of how water-related risks are identified, assessed, and managed across the Bay Area.

When staffing is reduced or funding is frozen, routine maintenance, calibration, and data analysis are often among the first activities to suffer.

As California’s 2025–26 flood season approached, state officials warned that pending federal cutbacks to the California–Nevada River Forecast Center could mean that forecasts, during large storms, get issued only once per day, instead of every six hours —reducing the state’s ability to track rapid changes during major storms (“Federal reductions to critical services threaten public safety as flood season gets underway in California,” Press Release, Office of Governor Gavin Newsom, Oct 2025).

The same press release noted that federal cuts have eliminated roughly one‑third of California’s manually measured snow‑survey courses, degrading the snowpack data water managers use to predict spring runoff, manage reservoirs, and anticipate flood risk.

California leaders have also highlighted that federal budget cuts and staff reductions could interrupt levee‑ and dam‑safety projects tied to past floods — such as work responding to the 2023 levee breach that flooded Pajaro (Monterey County) and upgrades slated for the American River, one of the most flood‑prone urban corridors in the country (“State Officials Say Federal Cuts Threaten California’s Environment,” LA Times, July 2025).

Bay Area climate activist, James Leach — author of two books about global warming and climate solutions – told me that downsizing staff and resources at relevant agencies could have real impacts locally:

If we don't get weather forecasts, we might find ourselves with surprise floods, and we may not have good information about excessive winds and not be prepared for it when they come in.

In practice, this means that cuts to staffing or research capacity do not simply degrade forecasts in a linear way.

Funding cuts can…

reduce the ability of forecasters to issue early alerts, update guidance as conditions change, or explain evolving risks to local agencies and the public

limit the availability of data needed to inform short- and long-range public planning and resilience efforts as well as policy initiatives

put public health and safety at risk by taking away the resources needed for the early detection of contamination risks from groundwater rise

Federal science programs also play a critical role in supporting regional coordination.

Many water systems in California cross city and county boundaries, linking upstream and downstream communities in ways that no single jurisdiction can fully manage alone.

Federal agencies often provide the regional-scale data and analysis that allow planners to see the full picture — whether that involves watershed-wide flood dynamics or the interaction between river flows and coastal conditions.

What Local Experts Told Us

According to experts interviewed for this series, local governments are rarely positioned to replace that capacity all on their own, although they did think that research universities, such as UC Berkeley, are likely to be involved already and could choose to fill voids created by federal spending cuts.

However, it’s still a fact that smaller cities and counties may lack the resources to maintain complex monitoring networks or to develop sophisticated models independently. When I spoke to retired Bay Area EPA scientist Emily Pimentel (MS Marine Ecology, SFSU), she emphasized just how transformative Biden-era EPA grants were for building out the green economy, including right here in the SF Bay region. Pimentel didn’t retire from her EPA post until shortly after the second Trump inauguration and was disappointed to see funding for these efforts abruptly eliminated.

EPA funding, said Pimentel, also supports important planning efforts:

You do need data to plan… where to put the wastewater treatment plant so it’s not going to be flooded. So that kind of data, which might be collected at a regional level may not be funded in those areas where you have a county or city government, so sometimes federal EPA grants help provide the funding to collect the data in those areas where there will otherwise be gaps.

As the federal priorities shift resources away from climate initiatives and agencies, research and access to it is likely to grow less equitable and more fragmented, with some areas well-studied and others increasingly opaque.

Pimentel was also concerned about the potential impact of EPA cutbacks on long-range planning as Bay Area municipalities and regional agencies roll out consequential adaptation and resilience blueprints.

For example, said Pimentel, EPA scientists often helped coordinate expert advisory support for planning and permitting processes in local jurisdictions — to ensure decision making was informed by local public input and adhered to broad EPA priorities and guidelines.

Retired Bay Area climate scientists Tom Murphree (PhD Atmospheric Sciences, former career climate scientist at the Naval Postgraduate School) and Eugenia McNaughton (PhD in Biology and career Quality Assurance Specialist with the EPA) both emphasized that gathering data for timely and advanced monitoring, modeling, and forecasting requires consistent research efforts, disciplined research methods, and cooperative, inter-agency data-sharing.

Murphree is concerned that federal cutbacks under the Trump administration “have made us less prepared by removing funding from the science that is needed to monitor the Earth’s [interconnected] climate systems and weather events and to help us get early warnings.”

When monitoring stations fall into disrepair, when datasets are interrupted, or when experienced staff leave without replacement, the effects can also persist long after budgets are restored.

Pollution Risks From Groundwater Rise

McNaughton also worries about how cuts to the EPA can impact public safety, with or without climate disasters, emphasizing that monitoring air and water quality takes consistent funding and resource allocations.

The stakes are higher when you factor in the ways that rainfall, floods, and sea level rise can contribute to the release, and migration of dangerous contaminants lodged in the soil.

The Toxic Tides project at UC Berkeley identified nearly 200 toxic sites at risk of flooding from groundwater rise, and much of this legacy toxic contamination disproportionately threatens lower income and disadvantaged communities (“SF Bay Sea Level Rise and Flood Strategy,” Save the Bay, Feb 2023).

These risks are not purely hypothetical.

McNaughton recounted an experience she had as an EPA scientist involved with teams responding to a mass water contamination event. Even when well funded, McNaughton lamented, detecting an influx of contaminants in air or waterways can be a very arduous and tricky process, sometimes difficult even for experts.

You have to have the grossest [highly consequential] effects, like when we saw all of these fish die, and birds die, in this case it was from selenium contamination… But when scientists from one of the responding agencies went out to examine, to get data, to get samples… they didn’t do the chemistry exactly right, and didn’t catch that selenium was the culprit.

Another federal agency then reviewed and reanalyzed the data and found high levels of bioavailable selenium in wildlife refuge water coming from drainage in certain central valley agricultural areas. Birds and fish died by the thousands, but this better understanding of the cause resulted in a twenty-year-long, federally and state-supported coordinated monitoring program working with farmers to reduce the selenium load to the refuge.

This is an example of the expertise these efforts require and how cutbacks that prevent adequate air monitoring and water testing efforts can mean increased risks — risks that might be prevented through earlier detection.

What this could mean down the road, McNaughton said, is that all of a sudden something of a much more significant level is happening before people find out there’s any new contaminant coming into the environment.

Moreover, added McNaughton, consistent ongoing research is also crucial for long-term policy and planning work:

Cutting EPA funding is like cutting off one of your arms… New toxins can come in and [only] be detected way later… and you’re cutting out the foundational kinds of research and research quality that would inform needed regulations and legislation.

— Eugenia McNaughton, PhD, retired EPA Scientist

Eugenia McNaughton is a retired environmental scientist who talked to us about the potential impacts that federal cuts to NOAA, FEMA, the EPA, and climate research could have on the Bay Area. McNaughton holds a PhD in Biology (with a concentration in Algal Cell Biology) from UC Santa Cruz and worked over twenty-five years, primarily on clean water initiatives in California, as a quality assurance specialist with the EPA.

The key takeaway here is clear enough: without reliable climate modeling and forecasting, communities lose the ability to plan ahead, prioritize smart investments, and reduce risk before impacts become unavoidable.

This is why sustained federal support for climate science, data collection, and forecasting capacity matters so much — when those systems are weakened, the planning tools Bay Area communities already depend on begin to erode just as climate risks are accelerating.

🔑 Without reliable climate modeling and forecasting, communities lose the ability to plan ahead, prioritize smart investments, and reduce risk before impacts become unavoidable. This is why sustained federal support for climate science, data collection, and forecasting capacity matters so much…

In a region already grappling with aging infrastructure, dense development, and complex geography, climate forecasting and modeling function as essential public safety tools. They help translate scientific knowledge into practical action — turning data into warnings, projections into plans, and uncertainty into manageable risk. When those tools are weakened, communities are left with fewer options and less time to respond.

Bay Area Topography: Where Water and Climate Risks Converge Locally

The Bay Area’s geography makes it especially sensitive to gaps in climate science, forecasting, and monitoring. Rivers, shorelines, and tidal systems intersect with dense development, aging infrastructure, and critical transportation corridors — creating risks that no single jurisdiction can manage alone.

The Bay–Delta: A Regional Stress Test

One of the clearest examples is the San Francisco Bay-Delta system. Spanning multiple counties and supporting ecosystems, communities, and infrastructure far beyond its boundaries, the Delta sits at the intersection of flood risk, sea level rise, and water management. Understanding how storm-driven river flows interact with tides — and how those dynamics may shift over time — depends on integrated, region-wide monitoring and modeling.

Experts interviewed for this series emphasized that federal climate science programs have long helped fill this coordination gap, providing basin-scale data and long-term projections that state and local agencies can build upon. When that capacity weakens, the burden shifts unevenly to jurisdictions that may already be stretched thin.

Shoreline Communities: Rising Baselines, Higher Stakes

Along the Bay’s edge, rising sea levels are steadily increasing baseline flood risk. Even without major storms, higher tides are beginning to affect low-lying neighborhoods and critical facilities. When storms do arrive, elevated sea levels can amplify flooding, pushing water farther inland and narrowing the window for response.

Inland Watersheds: Intense Rainfall, Fast-Moving Impacts

Farther inland, more intense rainfall is overwhelming creeks and stormwater systems designed for a different climate. In these areas, flood risk is often driven by timing — how quickly rain falls, how fast waterways rise, and whether infrastructure can keep pace.

Why Forecasting Matters for the Water Frontlines

Across all of these topographical contours and waterways, small differences in predicted rainfall totals or storm surge timing can translate into major differences on the ground — whether a roadway floods, a wastewater facility stays online, or emergency responders can reach affected neighborhoods.

In a region defined by interconnected waterways and shared infrastructure, weakened climate science does not affect just one city or county. Its consequences ripple outward, shaping how risks are identified, how resources are allocated, and how prepared the Bay Area can be for extreme weather events, sea level rise, and additional interwoven water-related challenges ahead.

Key Takeaways

Water is now a frontline climate risk in the Bay Area.

Heavier rainfall, more intense storms, and rising sea levels are increasing flood risk across the region — from inland creeks and urban streets to shoreline communities along the Bay.Forecasting and climate data are critical public safety tools.

Early warnings, emergency response coordination, and long-term planning all depend on reliable forecasting, modeling, and monitoring systems.Federal climate science plays an outsized role in local preparedness.

Many of the datasets and models local agencies rely on are supported at the federal level. When that capacity weakens, gaps emerge that cities and counties are often not positioned to fill on their own.The impacts of science and staffing cuts may be delayed but lasting.

Disruptions to monitoring networks, data continuity, and institutional expertise can undermine planning and preparedness over time — often becoming visible only when systems are stressed.Reduced forecasting capacity increases uncertainty just as risks grow.

As storms become more volatile and sea levels rise, communities have less margin for error. Losing early warning and planning tools makes it harder to anticipate and reduce harm.

Final Thoughts

As climate-driven water risks continue to intensify, the ability to anticipate and prepare for floods, extreme storms, and rising seas has never been more important. Across the Bay Area, heavier rainfall, more volatile storm patterns, and rising baseline water levels are already placing new pressure on infrastructure, emergency response systems, and long-term planning.

Throughout this post, one theme stands out: preparedness depends on a wide range of efforts — from data gathering that informs and guides short-term and long-range decision making for planning and adaptation, adequate warning systems, and well-trained and properly resourced emergency response providers.

In particular, managing water risks will rely on consistent climate forecasting, modeling, and monitoring. These efforts rely on sustained federal commitments to climate science capacity, long-term data continuity, and regional coordination — efforts that no single city or county can replace on its own.

In a region already grappling with aging infrastructure, dense development, and complex geography, climate forecasting and modeling function as essential public safety tools. They help translate scientific knowledge into practical action — turning data into warnings, projections into plans, and uncertainty into manageable risk. When those tools are weakened, communities are left with fewer options and less time to respond.

In a region defined by interconnected waterways and shared infrastructure, responding to water-related risks is complex — broad in scope but also highly varied in terms of specific, local risks and solutions. Understanding these connections is a critical step toward protecting communities and planning effectively and equitably.

That understanding also points toward action…

Public safety in the greater SF Bay Area Region will no doubt be impacted by federal cuts to agencies such as NOAA, FEMA, and the EPA. However, local residents and civic and business leaders can respond. The sections that follow highlight practical ways to stay informed, support science-based preparedness, and connect with tools and resources that help turn knowledge into action.

What You Can Do

Core actions to consider now:

Follow Climate Reality Bay Area’s newsletter and social channels for updates.

Share this post with neighbors, parent groups, community organizations, and local leaders. (Sign up here.)

If you have been impacted by wildfire or smoke, consider sharing your story in the comments.

Support and help inform local shoreline adaptation projects (city meetings, Bay Conservation and Development Commission hearings…).

Join a Climate Reality Bay Area Policy Action Squad other CRBA team that’s a fit for your interests and aptitudes — and get connected with other Bay Area residents advocating for climate action.

Join a Climate Reality Bay Area Policy Action Squad or connect with any other CRBA team that’s a fit for your interests and aptitudes.

Additional teams include:

community engagement

climate justice

green schools

communications

fundraising

events

and more…

However you connect, you’ll find a network of other Bay Area residents just like you — all looking for ways to make a difference.

Water-related action networks:

Below are some of the SF Bay Region groups you can support or connect with.

Save The Bay – Regional nonprofit focused on protecting and restoring San Francisco Bay, combining political advocacy, wetland restoration, and environmental education; offers regular shoreline restoration volunteer days and campaigns on sea level rise and equitable flood resilience.

San Francisco Baykeeper– Independent watchdog dedicated to protecting the Bay from pollution and holding polluters and government agencies accountable, including work on climate resilience and shoreline contamination that intersects with flooding and sea level rise.

SPUR (San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association) – Civic planning nonprofit that co‑developed the Shoreline Adaptation Atlas and runs public programs, reports, and advocacy campaigns on climate‑resilient land use, housing, and transportation that residents can plug into.

San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) – Science‑driven nonprofit that partners on projects like the San Francisco Bay Shoreline Adaptation Atlas and nature‑based shoreline solutions; while more technical, it regularly collaborates with community and agency partners and shares accessible reports and tools residents can use to understand local risks.

San Francisco Bay Regional CHARG (Coastal Hazards Adaptation Resiliency Group) – Regional collaborative focused on shoreline flooding and sea level rise; residents and community organizations can track its meetings and products to follow major adaptation projects and advocate for local priorities.

The Watershed Project — an East Bay nonprofit dedicated to protecting, conserving, and restoring the SF Bay watershed through hands-on education, habitat restoration, green infrastructure projects (like bioswales), and volunteer-driven monitoring of creeks and shorelines.

Coastal Quest – Bay Area Climate Resilient Coastal Communities – Nonprofit program that funds and supports frontline, community‑based groups in Contra Costa, Solano, Alameda, Marin and other Bay counties to advance equitable coastal and sea level rise resilience.

Local community‑based groups supported by Coastal Quest (e.g., Canal neighborhood groups in Marin County, Fresh Air Vallejo, All Positives Possible, Galilee Harbor, Atchison Village committees): Neighborhood organizations like these work on shoreline improvements, flooding and groundwater‑rise risks, and toxic‑site concerns.

Other resources:

Regional alerts and preparedness

AlertTheBay.org (regional alerts hub) — One‑stop site that links residents to each Bay Area county’s emergency alert system (including Oakland, San Francisco, San Jose) — sign upfor localized texts, calls, and emails about floods and other hazards

ABC7 Prepare NorCal (disaster preparedness resources) — A practical guide to building go‑kits for emergency evacuations, with links to Bay Area alert systems such as AlertSF for tsunami and flood warnings in San Francisco

California DWR(flood preparedness) — State overview of how floods happen, how to assess your risk, and what household supplies and plans can help save lives in storm seasons.

County and city emergency / flood agencies (partial list)

County Offices of Emergency Services, for local evacuation plans and alerts among other resources

San Francisco Department of Emergency Management (DEM) – Coordinates citywide response to disasters; issues Wireless Emergency Alerts, including flash flood and tsunami warnings

San Francisco Public Utilities Commission – Flood Maps & Resources – Interactive 100‑year storm flood map, “RainReadySF” tips, sandbag locations, and up to 100,000 in Floodwater Grants for eligible property‑level flood‑proofing

Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy — The Conservancy collaborates and cooperates with local communities and other parties to preserve, protect, and restore the natural resources, economy, and agriculture of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Suisun Marsh

San Mateo County Department of Emergency Management– Flooding Preparedness and Response – Explains how to find your Genasys/Zonehaven evacuation zone, county emergency contacts, and steps to take before and during flooding

OneShoreline – Countywide Flood Early Warning System (San Mateo County) – Public flood‑monitoring map showing real‑time creek, rainfall, and tide data with watch and warning levels to support both first responders and residents

For further reading:

The Sustainable Way: Straight talk about global warming — what causes it, who denies it, and the common sense transition to renewable energy (2016), by CRBA member James Leach.

The Renewable Way: Straight talk about restoring our climate, preventing untold suffering, and making a better world (2024), by CRBA member James Leach.

Soon to follow in this series:

How Federal Cuts Erode Local Resilience & Readiness

Click Below To Learn More About CRBA and How To Get Connected!